Setting the Record Straight on Health Care Funding in Canada

Is the responsibility for financing health care services being increasingly entrusted to private actors? Is there more private sector funding of care here than in Europe, as some maintain? Contrary to what certain commentators declare, we are not witnessing the gradual privatization of health care funding in Canada. This Economic Note demonstrates that this is a myth, at least when it comes to medically required care, which forms the core of our health care system.

Media release: The privatization of medically required care in Canada is a myth

Links of interest

Links of interest

|

|

|

| Health care lacks patient choice, competition (Sun Media, December 16, 2015) |

Setting the Record Straight on Health Care Funding in Canada

The question of the funding of health care continues to give rise to political debate in Canada. Last month, Saskatchewan authorized patients to pay out of their own pockets for MRI tests carried out in private clinics, previously the exclusive domain of the public sector.(1) Quebec, for its part, recently enacted a law designed to limit the fees that doctors will be able to charge for certain products and services deemed “ancillary,” whether for the opening of a medical file or the distribution of eye drops.

These decisions were met with indignation by certain activist groups and commentators.(2) According to such critics, these measures are further proof of the gradual privatization of the funding of health care in Canada.(3)

Is the responsibility for financing health care services being increasingly entrusted to private actors? Is there more private sector funding of care here than in Europe, as some maintain?

The Funding of Health Care Services in Canada

As in other countries, health care services in Canada are financed both by the public sector and by the private sector.(4) The amounts devoted to health care totalled nearly $210 billion for the country as a whole in 2013. Of this total, a little over 70% was covered by governments (almost entirely at the provincial level), with the remaining expenditures covered directly by patients or their private insurers.(5)

Under the Canada Health Act, each province’s public insurance plan must fully cover all spending for care that is considered medically necessary, whether delivered in hospital or in doctors’ offices, without direct contribution from patients that could reduce access.(6) Provincial public plans also fund what are considered complementary health care expenditures for certain segments of the population, including prescription drugs, long-term and home care, and transportation by ambulance.

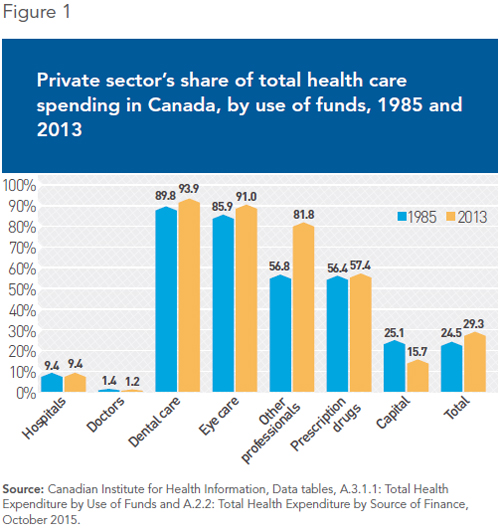

As for private health care spending, it essentially concerns areas that are peripheral to medically required care. This is the case for spending on care provided by dentists (94% private), by optometrists (91% private), and by other health professionals like psychologists, podiatrists, physiotherapists, and chiropractors (82% private). In addition, 57% of spending on prescription drugs is covered by patients or their private insurers (see Figure 1). In these areas, governments only finance expenditures for specific segments of the population, like young children, seniors, or welfare recipients.

Is Funding Increasingly Private in Canada?

Private spending as a share of total health care spending has increased somewhat since the Canada Health Act came into effect in 1984. Whereas it was 25% in the mid-1980s, it had risen to 29% by 2013, according to the data compiled by the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

It is private spending on care that is peripheral to the health care system that has increased the most, including dental care (+ 4 percentage points), eye care (+ 5 percentage points), and care delivered by other professionals (+ 25 percentage points). Private spending as a share of total spending in hospitals and doctors’ offices, the core of the universal health care system, on the other hand, remained unchanged during this period. When it comes to hospital expenditures, the private sector’s share was 9.4% in 2013, exactly the same proportion as it was in the mid-1980s.

This figure is misleading, however, since it does not actually concern medical treatments provided to Canadians. Indeed, it is primarily made up of spending by patients for private or semi-private rooms, television rentals, parking fees, or medical services not considered essential to health, like renting crutches or prostheses.(7) The only private spending for medically required care included in this data is spending by foreign patients.(8)

As for the amount spent privately for services in doctors’ offices, it represented between 0.9% and 1.6% of all expenditures for these services from 1985 to 2013. During this latter year, the share of private spending was 1.2%.(9)

Once again, there is a caveat: Certain services provided by doctors are not covered by the public insurance plans, simply because these services are not recognized as medically required. They concern, for example, the renewal of a prescription over the phone, or the delivery of medical certificates.(10)

Hence, medical and hospital services provided to Canadian patients are in fact practically 100% financed by the public sector,(11) and this situation has not changed in three decades.

Is There More Private Health Care in Canada Than Elsewhere?

It is relevant to ask how Canada compares with other industrialized countries when it comes to the participation of the private sector in the financing of health care. In the opinion of certain analysts, Canada is much closer to the United States than to the countries of Europe in this regard.(12) What is the reality?

When we look at total health care spending, we see that the private sector’s share in Canada is similar to what it is in Australia, Spain, and Switzerland, but higher than it is in Germany, France, and the Scandinavian countries.(13) It is far lower than what it is in the United States, though, which of course does not have a universal health care system, unlike Canada and the vast majority of OECD countries.(14)

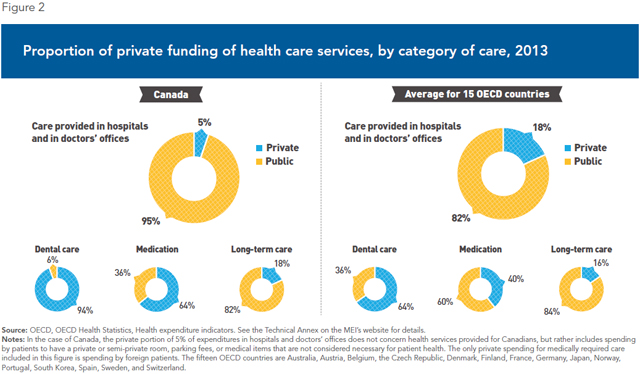

However, when health care funding is broken down by spending category, it becomes obvious that Canada is the odd one out, compared to the countries of Europe, in so severely restricting private financing for care that is considered medically required, namely the care provided in hospitals and in doctors’ offices.

For example, around 20% of hospital care is privately financed in Switzerland and Belgium, and nearly 30% in Australia. When it comes to care provided in doctors’ offices, the share of private funding is greater than Canada’s in all countries, representing even more than 20% in most countries, including Sweden (22%), France (27%), and Finland (56%). An analysis of health care spending in 15 OECD countries shows that on average, 18% of funding for care provided in hospitals and in doctors’ offices in these countries comes from private sources (see Figure 2).

These are not, contrary to certain beliefs, “two-tier” health care systems, but rather mixed health care systems where no citizen is excluded from universal insurance coverage. Moreover, the other OECD countries generally provide public insurance covering a much wider range of health care services than what is covered in Canada.(15)

The data on the private funding of care do not provide a complete picture of the differences between the Canadian system and systems elsewhere in the world. The greater participation of the private sector in other countries is also evident in the provision of care. Indeed, in most other countries, patients can choose to be treated in public hospitals or private hospitals.(16) Not in Canada, however, where 99% of hospitals are public.(17)

In fact, every other OECD country provides more hospital services through the private sector than Canada—even those where private funding is only a small proportion of total funding. For instance, although private funding of hospital care remains modest in France and Finland (between 7% and 9% according to data from the OECD), all French and Finnish patients have the option of being treated in private hospitals, for-profit or not, paid for by their public insurance.(18) This is what explains that 55% of surgeries in France are performed in private for-profit clinics, which represent nearly 40% of medical facilities with hospitalization capabilities.(19)

Conclusion

For the past few years, several commentators have been insisting on the fact that the share of private funding in total health care spending is increasing in Canada, and is higher than elsewhere. They imply that this trend threatens universality of care.

It is true that the proportion of private funding has gone up over the past three decades when it comes to peripheral health services—areas characterized by innovation and quality services, where waiting lists are nonexistent.(20) A more careful analysis of the data shows, however, that this is not at all the case when it comes to the core of the health care system, which is to say those services that are provided in hospitals and doctors’ offices. The public monopoly maintains an absolute stranglehold on these services in Canada.

No other OECD country, in Europe or elsewhere, so severely restricts the participation of the private sector in the provision and funding of medically required health care services. While fully respecting the principle of universality, these mixed systems generally manage to achieve much better results than Canada in terms of patients’ access to these services.

By fostering confusion about the distribution of public and private health care funding, supporters of the status quo obscure a basic fact at the root of our structural waiting list problem, namely the lack of competition and patient choice in our public health care system. It is crucial to set the record straight in this regard if we want to correctly diagnose the problem and apply the remedies that are appropriate.

This Economic Note was prepared by Yanick Labrie, Economist at the Montreal Economic Institute and holder of a master’s degree in economics (Université de Montréal). The MEI’s Health Care Series aims to examine the extent to which freedom of choice and private initiative lead to improvements in the quality and efficiency of health care services for all patients.

References

1. Emma Granney, “Bill to partially privatise MRIs in Saskatchewan passed by government,” Regina Leader-Post, November 3, 2015.

2. Élisabeth Fleury, “Pétition contre les frais accessoires à l’Assemblée nationale,” Le Soleil, November 27, 2015; Roxane Léouzon, “527 témoignages contre les frais accessoires,” Métro, November 15, 2015; Brent Patterson, “Saskatchewan passes Bill 179, the MRI Facilities Licensing Act,” The Council of Canadians, November 10, 2015.

3. Astrid Brousselle et al., “Why Trudeau must save Medicare in Quebec,” Toronto Star, November 5, 2015; Thierry Haroun, “La privatisation du secteur de la santé est en marche,” Le Devoir, November 28, 2015.

4. Obviously, all health care expenditures are ultimately funded by individuals, whether in their role as taxpayers, as insured parties, or as consumers. Therefore, when speaking of the financing of health care services by the public or private “sector,” it is a question of who is responsible for the payment of expenditures.

5. Canadian Institute for Health Information, Data tables, A.3.1.1: Total Health Expenditure by Use of Funds and A.2.2: Total Health Expenditure by Source of Finance, October 2015.

6. The concept of “medically required” care has never been clearly defined by federal or provincial legislation, but has historically been interpreted by provincial governments as being care provided in hospitals and doctors’ offices. See J.C. Herbert Emery and Ronald Kneebone, The Challenge of Defining Medicare Coverage in Canada, The School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, SPP Research Papers, Vol. 6, No. 32, October 2013.

7. Canadian Institute for Health Information, Exploring the 70/30 Split: How Canada’s Health Care System Is Financed, September 2005, p. 49. See also Canada Health Act, Frequently Asked Questions, What health care services are not covered by provinces and territories?

8. See among others the high profile case of a foreign patient who paid a large sum of money to undergo her procedure sooner in Quebec in 2013. Vincent Larouche, “Une Koweïtienne opérée au CUSM : des soins VIP pour 200 000 $,” La Presse, February 1st, 2013.

9. Op. cit., footnote 5.

10. Canadian Institute for Health Information, op. cit., footnote 7, p. 53.

11. Livio Di Matteo, “Policy Choice or Economic Fundamentals: What Drives the Public-Private Health Expenditure Balance in Canada?” Health Economics, Policy and Law, Vol. 4, 2009, p. 32; André Picard, “Honest talk about private health services is long overdue,” The Globe and Mail, November 10, 2015.

12. Colleen M. Flood, “Privatization is not the answer to Canada’s health care woes,” The Moncton Times & Transcript, July 29, 2014.

13. OECD, OECD Health Statistics, Health expenditure indicators.

14. OECD, Health at a Glance 2015, OECD Indicators, November 4, 2015, p. 121.

15. Åke Blomqvist and Colin Busby, “Rethinking Canada’s Unbalanced Mix of Public and Private Healthcare: Insights from Abroad,” Commentary No. 420, C.D. Howe Institute, February 2015, p. 21. See the Technical Annex on the MEI’s website for the complete data for 15 OECD countries in this regard.

16. Pedro Pita Barros and Luigi Siciliani, “Chapter Fifteen – Public and Private Sector Interface,” in Mark V. Pauly et al. (eds.), Handbook of Health Economics, Vol. 2, 2011, p. 989.

17. OECD, OECD Health Statistics, Health care resources: hospitals, 2012.

18. Grégoire de Lagasnerie et al., Tapering Payments in Hospitals: Experiences in OECD Countries, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 78, March 2015, p. 14.

19. Bénédicte Boisguérin and Gwennaëlle Brilhault (coord.), Le panorama des établissements de santé : édition 2014, Government of France, Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques, March 2015, pp. 83 and 111.

20. See Yanick Labrie, The Other Health Care System: Four Areas Where the Private Sector Answers Patients’ Needs, Research Paper, Montreal Economic Institute, March 2015.